While an entirely Christian holiday, Saint Patrick’s Day (The Feast of Saint Patrick) is a moment in the United States and its colonies for Irish-Americans to be proud of their cultural heritage.

As a cultural celebration, St. Paddy’s Day (not Patty’s) goes as far back as 1737. Irish Protestants (not Catholics) were the first to organize events for charity and Irish soldiers in the British army marched on parade in 1766. The practice of celebrating the day flourished during the Great Famine in Ireland, contributing to the Irish Diaspora when Irish immigrants came to the U.S.

While the popular narrative of Irish becoming enslaved at this point in history, research has debunked this myth and highlighted it as a ruse to delegitimize the history of chattel slavery of African people in the U.S. It is now a trope used by white supremacists.

Before the Naturalization Act of 1906, immigration into the U.S. was a two-step process for all white people (preferably men) who came through Ellis Island. The racist policies of the time did discriminate against non-white immigrants through the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Page Act, and later on in 1920 with the Emergency Quota Act.

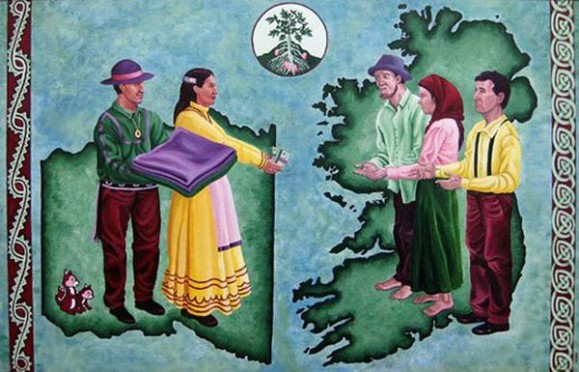

During Irish immigration to the U.S., however, there exists a moment of solidary between an Indigenous community and the people of Ireland.

The Chahta (Choctaw) lived in present-day Mississippi/Alabama/Louisiana during the westward expansion in an era filled with policies, broadly under the banner referred to as Manifest Destiny. Between the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the final years of the Trail of Tears in 1850, over 60,000 tribal citizens from the “Five Civilized Tribes” were forcibly removed by military forces of the United States to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, the homelands of the Caddo, Quapaw, Osage, and Tonkawa. As many as 16,500 elders, women, children and men would die en route.

The Chahta themselves lost 2,500 citizens during this death march, experiencing at least 15 percent of the total deaths of the Trail of Tears.

Experiencing such an atrocity would not kill the empathy of Indigenous people, however.

When crops began failing in 1845 in Ireland due to an infestation, over one million Irish would go onto die from malnutrition and starvation. During this time, in 1847, the Chahta collected $170 (over $5,000 today) and sent the relief funds to Ireland to try to help alleviate the suffering.

It remains an historic example of how Indigenous people have come to understand suffering and rather than choose to inflict more or ignore it completely, choices are made to empathize and do what can be done.

In the early 1990s, cultural exchanges between the Choctaw Nation and the Republic of Ireland began, including the commissioning of a monument. In 2018, Leo Varadkar, Ireland’s Taoiseach (Prime Minister), visited Choctaw Nation tribal headquarters. He said:

“A few years ago, on a visit to Ireland, a representative of the Choctaw Nation called your support for us ‘a sacred memory’. It is that and more. It is a sacred bond, which has joined our peoples together for all time.”

WHY THIS MATTERS

Today, in the United States political realms, the Nativists who incited fear of all immigrants have been succeeded by the MAGA (Make American Great Again) movement in the Republican party. Our national ire is directed at immigrants from the Spanish-speaking geographies of Mexico, Central America, South America, and has even grown to include Asians and anyone from the Farsi- and Arabic-speaking world. Across Indian Country in 2024, many activists were in solidarity with the Palestinian people, as their homelands were razed by the bombing of occupying forces, and initiating a forced relocation from their homes, schools, and communities.

The cycle repeats when global change is afoot.

Personally, I use the Edelman Trust Barometer to help me make sense of the current mood of the world, to give full context. Because when we know what we’re dealing with, we can plan accordingly. Beyond what we know is happening now, we know that the restoration of good relations after this presidential administration relies on receiving and believing what’s true about what happened.

Documenting the histories of moments of solidarity are helpful and make an impact. In the long-run, they matter because they highlight our shared humanity in the face of dehumanizing polarization.

Leave a comment